Helpful Hints for People With Choice Blindness

Some options are obvious, like “Would you like anchovies or pepperoni on your pizza?” (For example, “Are you planning to purchase an Amazon Echo or a Google Home?”). However, most of us want to believe that we “know our own mind”—that is, we are crystal clear when deciding. Swedish psychologists have shown that we shouldn’t always trust our understanding.

When we make a choice but forget about it right after, we suffer from choice blindness. An example of choice blindness would be going to an ice cream shop to get a chocolate cone but unknowingly accepting a strawberry one.

Go to an electronics store and pick out a new 55-inch Vizio TV, but then you’re committing choice blindness when they bring out the much more costly 55-inch Sony TV. A case of choice blindness would be ordering burgers and fries but failing to see the soup and salad option that comes with it.

Choice Blindness

You can see that Johannson, Hall, and colleagues[1] developed a way to induce choice blindness in a controlled environment. Still, their goal was broader than just showing that individuals may forget their decisions. Their mission as psychologists is to delve into a fascinating phenomenon (choice blindness) to deduce its causes and draw any new conclusions about the human brain.

The Findings of the Research

Johansson, Hall, Sikstrom, and Olsson conducted a seminal study on decision blindness, the tendency for individuals to fail to notice discrepancies between their goals and the results. As part of the research, subjects looked at two photos of female faces for two to five seconds each. The next step was for the participants to choose the most gorgeous face.

After the participants believed they had selected a photo, the researchers showed them a different lady. They asked them to explain what made her appealing.

13% of the participants barely detected the changeover, which is somewhat surprising. 1 Many even went so far as to explain why they found the face appealing, even though it was not the woman they had selected.

Subsequent studies showed the potential impact of these effects on other decision-making processes. In 2010, researchers Petter Johansson and Lars Hall presented this same situation to volunteers at a supermarket.

Fewer than 20% of people who tried the jam rejected it seconds before actually realising it had tasted that way. The contrast between the two tastes varied greatly, from hot to sweet to bitter.

On other occasions, individuals found themselves tasting the identical jam twice. But when pressed, they would describe the dissimilarities between the two flavours.

The Trial by Peter Johansson

When individuals fail to recognise their preferences and decisions, this is called choice blindness. Lars Hall and Peter Johansson’s paper further explains this phenomenon.

- Choice The introspection illusion encompasses blindness as one of its manifestations. In this case, individuals mistakenly believe they can see the source of their own mental states and dismiss the introspections of others as untrustworthy.

- Consider this perspective on choice blindness. In our minds, we desire A, but when presented with B, we devise many excuses to justify why B is superior and prove that we really desired it all along.

- The research by Lars Hall and Peter Johansson provides a more thorough explanation of choice blindness.

Issue Description

- Peter Johansson and his colleagues used a novel approach to study people’s self-awareness regarding their preferences.

- During and after the trial, the researchers wanted to see if individuals realised their decision was incorrect.

- Technical Approach

- Scientists asked participants to pick two images of women’s faces that were most appealing.

- When closely examined, The students were asked to describe their “chosen” image vocally.

A total of fifteen trials were conducted with different pairs of faces to gauge the watch volunteer’s performance. However, a card magic trick was employed in three trials to secretly switch out one face for the other once the subjects had decided.

People who didn’t want to end up with a particular face ended up with it. Even if it wasn’t their initial pick, they were again forced to justify their choice of face.

Final Product

Most people who participated in the experiment didn’t realise that the image they viewed differed from the one they had initially selected. Lots of people came up with elaborate justifications for their choices.

- The topic may state:

- Because blondes are my favourite, I went with this one.

- Even though he specifically requested a brunette, he ended up with a blonde. They had to have been confabulated because they explained a choice they never made.

If The Result of a Choice Were to Alter Dramatically, We Would all Notice.

Contrary to expectations, participants should have noticed the discrepancy in 75% of the trials. Not only that but when given extra time to think about their choice—which they had first rejected—they came up with elaborate justifications for why they went with that face.

- This is particularly intriguing because many participants had no idea about the swap. The experimenters coined the term choice blindness to describe this inability to notice a discrepancy.

- Only around 10% of the modifications were evident to the subjects. By the time each experiment ended, only around 20% of the manipulations had been revealed.

A Hypothetical Situation was Provided to the Participants After the Experiment:

Consider a scenario in which you participated in an experiment, but the faces you selected were reversed. Does this occur to you?

- In a follow-up interview, 84% of people stated they would. The researchers dubbed it choice blindness. Specific individuals showed shock and even disbelief upon learning the reality.

- Johansson elaborates that people continued to verbalise their decisions confidently, maintained the same emotional state, and provided the same description for those they had selected and those they had not.

- The impacts of choice blindness extend beyond hasty decisions, another significant result. Whether participants provide brief or detailed explanations, numerical ratings or labels, and so on in response to the mismatched choice outcomes, this interaction could influence their future preferences to the point where they start to favour the previously rejected alternative.

- Since self-feedback (“I picked this, I publicly said so. Therefore I must like it”), The intricate nature of developing shared preferences can be attributed to several questionable factors. However, these factors provide researchers with a unique insight into the complex dynamics of the process.

- Researchers are unsure exactly what causes choice blindness. Still, they believe it has far-reaching implications for our decision-making processes. One of the researchers, Hall, claims that choice blindness isn’t universal. As a result, we need to rethink and study intention in more depth.

Johansson’s research disproves several decision-theory assumptions, including the idea that we can always tell when our goals and the results of our actions do not align. His experiment also calls into question common-sense ideas of free will and self-awareness, as well as established decision-making theories.

Application

Subjectivity and introspection, formerly thought to be exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, to investigate scientifically, may now be explored through experiments on choice blindness.

Why is this occurring? Confabulations, argues Jonah Lehrer, are sometimes the only half-truths that may keep one’s identity intact. According to Lehrer, “we construct a sense of being” like a novelist constructs a story. The self is like a piece of art; it’s a creation of our minds that helps us make sense of our disjointed parts.

Decisions Affected by Choice Blindness

It has been shown that choice blindness affects visual, gustatory, and olfactory preferences, but might more consequential decisions also be affected?

- Hall and coworkers examined the effects of choice blindness on political beliefs in a 2013 study. The Swedish general election included questions to gauge participants’ opinions on several wedge topics and their stated voting intentions.

- The researchers then used deception to change their responses to reflect the opposite political stance. After that, they were given new questions and asked to explain their answers.

- More than 90% of participants accepted and endorsed at least one changed response. Still, only 22% of the manipulated replies were identified, which aligns with previous studies on choice blindness.

Where Does Choice Blindness Come From?

Can you tell me how experts define choice blindness? Johansson and Hall claim that when given an option that isn’t our first preference, we often rationalise it by saying it was only a “choice.”

Why do many individuals ignore these toggles? Do our preferences go unnoticed more often than we believe?

One such component is interest in the decision at hand. When we think more about a problem, discrepancies between our choices and the results we obtain may become more apparent. Another factor is how close the options are; when given a decision we didn’t select, we can be less inclined to notice subtle distinctions.

Practical Consequences

- The real world may be significantly affected by choice blindness. RecognizingRecognizing faces is a skill that is crucial for our daily lives. Despite our confidence in our ability to recall previously chosen faces, our ability to detect switching could be much better.

- There are instances when this type of error can profoundly impact one’s life, even if it might not always be substantial. One of the most prevalent ways to identify the alleged criminal in a case is through eyewitness testimony.

- Nevertheless, DNA evidence is significantly more reliable than this type of testimony, no matter how convincing it seems.4 It may be more straightforward than we believe to influence a witness into affirmatively and firmly identifying the incorrect person, even if they have no ill will against the accused.

- Thinking about and absorbing your options before deciding can be helpful the next time you need to pick one. In the future, you could confuse that option with something else.

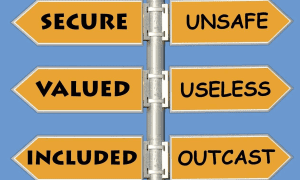

Do You Have a Good Grasp Of Who You Are?

- When faced with a decision between two options, whether two faces or two politicians, you could feel confident in your reasoning for choosing A over B. On the other hand, are you? If you ask a Swedish psychologist, she would say no.

- You are requested to rank the subject’s attractiveness based on your perception of two images, which might be of two men or two women. I can handle that. However, the next question is to request an explanation as to why.

- Now that’s more challenging. It might provoke contemplation. What is it about her that appeals to you? Do you think her eyes have any allure? Even her locks? Why does he seem different? His powerful jawline and flawless teeth appeal to you.

- However, do you genuinely believe these are why you found one individual more appealing than the other? Your doubts may grow when you learn about Prof. Petter Johansson’s work.

- Prof. Johansson conducted an additional experiment before the most recent US election, which was the highly disputed 2016 presidential race between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton.

- He had them rank the candidates based on character and experience; then, he swapped their scores, giving the one they despised a higher score. The result was satisfactory. Several explained why they felt ambivalent about one or the other.

- Surprisingly, the effects of such deception are long-lasting. When you show someone both faces simultaneously, you can trick them into thinking blond hair is more appealing than brown; they’re likely to reinforce their choice.

- The same holds true for one’s political beliefs. He tested their opinions the week after Petter Johansson influenced his participants’ political decisions. Evidently, “they had listened to their own arguments” after being forced to defend their new views.

How Reliable are Your Own Preferences?

- The techniques used by conjurers have several psychological underpinnings, which distort our perspective, manipulate our attention, and even impact our decision-making. Nowadays, these forms of magic are seen as a fresh way to learn about the mind.

- In fact, researchers may learn a lot about the mechanisms underlying transcultural, social, cognitive, and developmental processes by observing magic acts (Kuhn, Amlani, & Rensink, 2008).

- Through magic’s conjuring techniques, we can have experiences that defy our expectations. Conjurers have perfected deceptive psychological techniques to produce captivating illusions that defy our rationality throughout history.

Furthermore, magicians have mastered several strategies that challenge the audience’s preconceived notions about what is possible. They typically make claims about, among other things, being able to subtly influence people’s actions or ideas. Mind magic is performance magic that can occur in various settings.

Some artists claim to have psychic or paranormal powers. In contrast, others present it as a psychological talent, like reading the audience’s body language or employing subtle suggestions. Using mentalism tools, a subfield of psychology has recently uncovered an intriguing mechanism of choice blindness.

If you feel generous, please support me as a writer by subscribing to my website and following me on social media. I would highly appreciate that. Please like, share and comment for my further support. Thank you so much for your precious time.